(ማስታወቂያ)

(ማስታወቂያ)

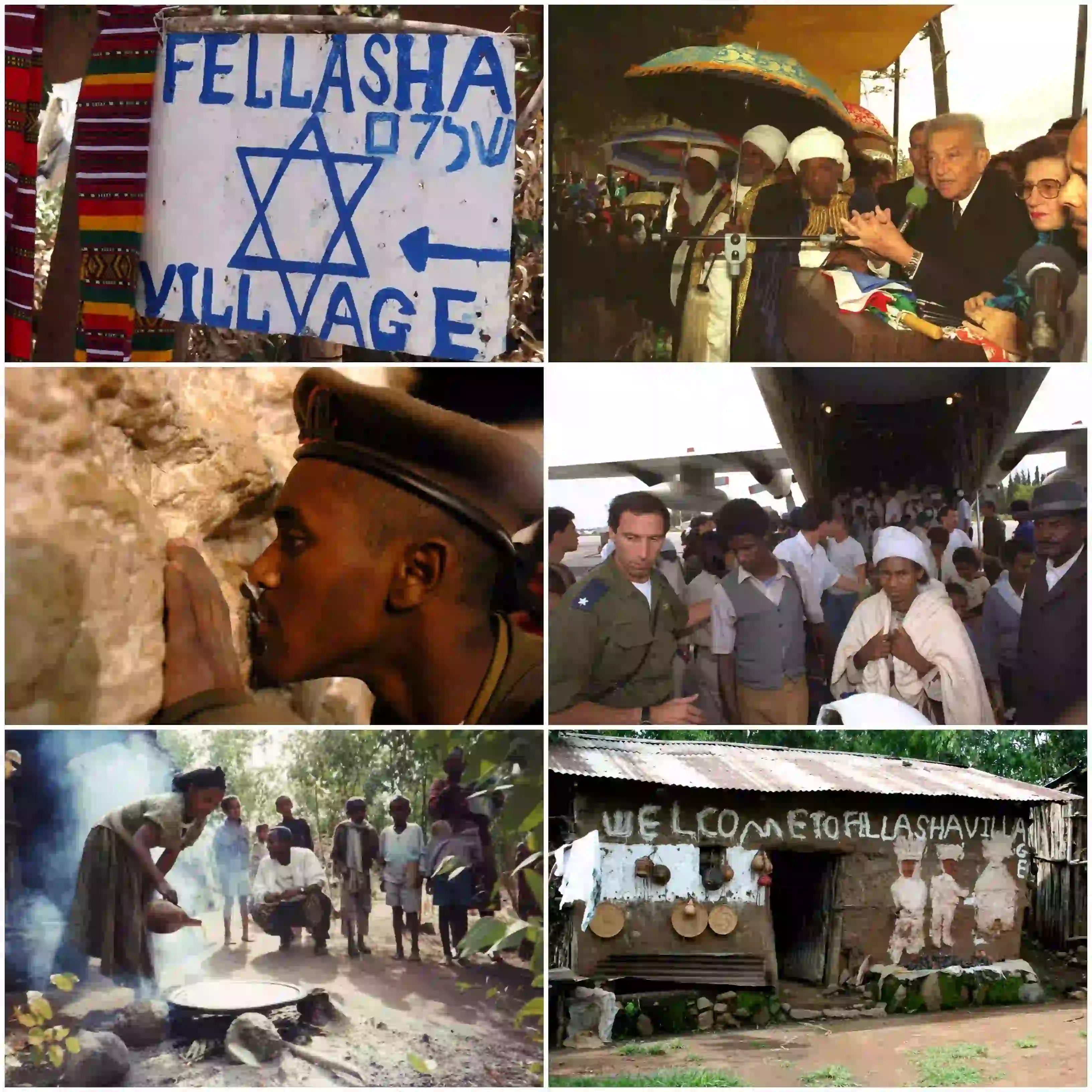

In the fascinating tapestry of Jewish history, the Beta Israel, also known as Ethiopian Jews, weave a remarkable narrative of resilience, isolation, and perseverance. Their story unfolds in the ancient lands of the Kingdom of Aksum and the Ethiopian Empire, now nestled within the modern-day Amhara and Tigray regions of Ethiopia. For centuries, the Beta Israel thrived alongside predominantly Christian and Muslim populations, residing in over 500 small villages scattered across the northern and northwestern regions of Ethiopia.

The story of Ethiopian Jews, also known as Beta Israel, is a remarkable testament to resilience, faith, and the pursuit of a homeland. From their ancient roots in Ethiopia to their challenging journey to Israel, the Beta Israel community has faced numerous trials and triumphs. In this article, we will see 27 important facts that shed light on the history, struggles, and contributions of Ethiopian Jews. From their immigration to Israel during daring rescue operations to the ongoing challenges they face in integration, these facts aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of the Ethiopian Jewish experience. Join us on this informative exploration as we uncover the rich tapestry of Ethiopian Jewish heritage and their ongoing journey towards full participation in Israeli society.

This region served as their ancestral homeland, where they developed their unique Jewish identity and practices.

These villages were spread across a wide territory and were inhabited alongside predominantly Christian and Muslim populations. Despite living in close proximity to other religious communities, the Beta Israel maintained their distinct Jewish identity.

They followed their own religious customs and rituals, differing from mainstream Jewish communities. In Israel, their unique form of Judaism is referred to as Haymanot (a colloquial term for "faith").

Their geographical location and limited interaction with the outside world contributed to their isolation. This isolation allowed them to develop their distinct practices and traditions over the centuries.

The origin of the term is not entirely clear, but it was used to describe the community based on certain perceptions or stereotypes held by the emperor or others at the time. However, over the years, the term "Falasha" has come to be considered offensive and derogatory. It is no longer used to refer to the Beta Israel community, as it carries negative connotations and does not accurately represent their identity or history. The community prefers to be referred to as Beta Israel or by other names that affirm their Jewish heritage and connection to the broader Jewish community.

They endured significant pressure to convert to Christianity, particularly during this period. Many members of the community were coerced into abandoning their Jewish faith and embracing Christianity.

These individuals are descendants of those who converted to Christianity under duress. Over time, some members of the Falash Mura community expressed a desire to return to their Jewish roots and rejoin the Beta Israel community.

This Christian community shares historical ties and cultural similarities with the Beta Israel, indicating a historical connection between the two groups.

Scholars and religious authorities engaged in discussions and examinations of Jewish law (halakha) and constitutional matters to determine whether the Beta Israel should be recognized as Jews.

This decision granted the Beta Israel the right to immigrate to Israel and become citizens under the Law of Return, which grants automatic citizenship to Jews and their immediate family members.

Operations such as Operation Brothers, which took place in Sudan between 1979 and 1990, and Operation Solomon, conducted in the 1990s from Addis Ababa, played crucial roles in transporting and resettling Ethiopian Jews in Israel.

Historical pressures during this period played a significant role in their formation.

Some accounts claim they are descendants of the Tribe of Dan who migrated to Ethiopia, possibly led by the sons of Moses during the time of the Exodus. Other traditions mention events like the split of the Kingdom of Israel or the Babylonian Exile as potential origins.

According to this version, they migrated to Egypt after the destruction of the First Temple, then moved to South Arabia (Yemen), Sudan, and eventually settled in Ethiopia with the assistance of Egyptian traders. Later, another group arrived during the reign of King Kaleb after he conquered Yemen.

According to their oral traditions, they trace their origins to various sources, including migration from the Tribe of Dan led by the sons of Moses, events like the split of the Kingdom of Israel or the Babylonian Exile, and independent migration routes to Ethiopia via Egypt, South Arabia (Yemen), and Sudan.

Eldad claimed to come from a Jewish kingdom of pastoralists far to the south and spoke a previously unknown dialect of Hebrew. He stated that the Jews of his kingdom descended from the Tribe of Dan and had fled the civil war in the Kingdom of Israel, settling in Egypt before moving southwards up the Nile into Ethiopia. This supports the Beta Israel's claim of being descended from the Danites. Other sources mention Jewish prisoners of war brought from ancient Israel by Ptolemy I and settled on the border of his kingdom with Nubia (Sudan). Some accounts also describe migration routes through Qwara in northwestern Ethiopia or via the Atbara River from Egypt.

The most common paternal lineage among Ethiopian Jews is haplogroup A, which is carried by approximately 41% of Beta Israel males. This lineage is primarily associated with Nilo-Saharan and Khoisan-speaking populations. The specific A-Y23865 variety found in Ethiopian Jews originated about 10,000 years ago and is localized to the Ethiopian highlands and the Arabian Peninsula. There is a significant genetic difference of 54,000 years between Ethiopian Jews and the Khoisan population.

About 18% of Ethiopian Jews carry the E-P2 lineage, with most belonging to the E-M329 subclade. This lineage has also been found in ancient DNA from a 4,500-year-old Ethiopian fossil. Such haplotypes are common among Omotic-speaking populations in southwestern Ethiopia.

A mitochondrial DNA study conducted on Beta Israel revealed that 51.2% of their maternal ancestry belongs to the macro-haplogroup L, typically found in Africa. The remaining maternal lineages consisted of Eurasian-origin lineages such as R0 (22%), M1 (19.5%), W (5%), and U (2.5%). There was minimal gene flow observed between the Yemenite and Ethiopian Jewish populations, suggesting distinct maternal population histories. The maternal ancestral profile of the Beta Israel is similar to that of highland Ethiopian populations.

A study by Behar et al. (2010) found that Ethiopian Jews cluster with neighboring populations in Ethiopia, specifically the Amhara and Tigrayans, despite a paternal link between the Bene Israel and the Levant. This suggests that the origins of most Jewish Diaspora communities can be traced back to the Levant.

A study by Ostrer et al. (2012) suggests that the Ethiopian Jewish community was founded about 2,000 years ago by a small number of Jews from elsewhere, with local populations joining the community and contributing to their genetic distinctiveness. Additionally, a 2020 study by Agranat-Tamir et al. indicates that the DNA of Ethiopian Jews is predominantly of East African origin, but approximately 20% of their genetic makeup shows similarity to Middle Eastern Semitic populations, modern Jewish and Arab populations, and Bronze Age Canaanites.

Some believed they were direct descendants of Jews who lived in ancient Ethiopia, whether from an Israelite tribe or through conversions by Jews in Yemen or the Jewish community in southern Egypt at Elephantine. Marcus Louis suggested that the ancestors of the Beta Israel were related to the Asmach, an Egyptian regiment that migrated or were exiled from Elephantine to Kush and settled in Sennar and Abyssinia. In the 1930s, Jones and Monroe pointed out that several Abyssinian words related to religion have Hebrew origins, indicating a possible antiquity of Judaism in Ethiopia. Richard Pankhurst summarized various theories about the origins of the Beta Israel, including converted Agaws, Jewish immigrants intermarrying with Agaws, immigrant Yemeni Arabs or Yemeni Jews, Jews from Egypt, and successive waves of Yemeni Jews. Traditional Ethiopian scholars declared that they were Jews before Christians, while more recent Ethiopian hypotheses emphasize the conversion of Christians to the Falasha faith, indicating that the Beta Israel were an Ethiopian sect comprising ethnic Ethiopians.

Jacqueline Pirenne suggested that Sabaeans, who fled south Arabia to escape Assyrian devastation of Israel and Judah in the 8th and 7th centuries BCE, migrated to Ethiopia, with a second wave occurring in the 6th and 5th centuries BCE to escape Nebuchadnezzar II, including Jews fleeing the Babylonian takeover of Judah. These Sabeans later departed from Ethiopia to Yemen. Menachem Waldman proposed that a significant emigration from the Kingdom of Judah to Kush and Abyssinia occurred during the Assyrian siege of Jerusalem in the early 7th century BCE. According to Rabbinic accounts, a group of Judeans joined Sennacherib's campaign against Tirhakah, king of Kush, and were lost in the mountains, potentially identified with the Simien Mountains. In 1987, Steve Kaplan highlighted the lack of fine ethnographic research on the Beta Israel and the limited attention given to their recent history by researchers. He noted that many individuals, including politicians, journalists, rabbis, and political activists, have attempted to propose solutions to the mystery of their origin. By 1992, Richard Pankhurst concluded that the early origins of the Beta Israel, known as the Falashas at the time, remained shrouded in mystery due to a lack of documentation, and it is likely to remain so indefinitely.

By 1994, two main views emerged:

Some scholars support the hypothesis that the Beta Israel have an ancient Jewish origin and have preserved certain Jewish traditions within the Ethiopian Church. Supporters of this view include Simon D. Messing, David Shlush, Michael Corinaldi, Menachem Waldman, Menachem Elon, and David Kessler.

Another hypothesis suggests that the Beta Israel underwent a process of ethnogenesis between the 14th and 16th centuries. According to this view, a sect of Ethiopian Christians adopted practices from the Old Testament and eventually identified as Jews. Steven Kaplan is a proponent of this hypothesis, along with G. J. Abbink, Kay K. Shelemay, Taddesse Tamrat, and James A. Quirin. However, Quirin differs from other researchers by assigning more weight to the possibility of an ancient Jewish element that the Beta Israel have conserved. Certain practices observed by Ethiopian Jews differ from rabbinic practice but align with the practices of late Second Temple sects. This suggests that the Beta Israel may possess a tradition rooted in ancient Jewish groups that have become extinct in other regions.

In late 1984, the Sudanese government, following the intervention of the U.S., allowed the emigration of 7,200 Beta Israel refugees to Europe, who then made their way to Israel. The first of these two immigration waves, known as Operation Moses (originally named "The Lion of Judah's Cub"), took place between November 20, 1984, and January 20, 1985. It brought 6,500 Beta Israel to Israel. This operation was conducted in secret and involved the Mossad and other agencies, evacuating Jews from Sudan.

Following Operation Moses, another operation called Operation Joshua (also referred to as "Operation Sheba") was conducted by the U.S. Air Force. It took place a few weeks after Operation Moses and aimed to bring the remaining 494 Jewish refugees from Sudan to Israel. This operation was carried out due to critical intervention and pressure from the United States.

Although the emigration of the Beta Israel community was officially banned by the Communist Derg government of Ethiopia during the 1980s, it is now known that General Mengistu collaborated with Israel. In exchange for money and arms, General Mengistu granted the Beta Israel safe passage during Operation Moses. This collaboration facilitated the rescue and migration of thousands of Beta Israel members from Ethiopia to Israel, despite the official ban on their emigration.

After the collapse of Communism in Central and Eastern Europe, the Ethiopian government allowed the emigration of 6,000 Beta Israel members to Israel in small groups. This was primarily to establish ties with the U.S., Israel's ally. Many more Beta Israel members sought refuge in Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, to escape the civil war in their region of origin and await their turn to immigrate to Israel.

In 1991, as Ethiopia faced political and economic instability, the Israeli government, along with private groups, resumed migration efforts. Over a span of 36 hours, a total of 34 El Al passenger planes, with seats removed to maximize capacity, airlifted 14,325 Beta Israel members non-stop from Ethiopia to Israel.

Throughout these years, the Qwara Beta Israel community immigrated to Israel. Additionally, another 4,000 Ethiopian Jews who had failed to reach the assembly center in Addis Ababa in time were flown to Israel in subsequent months.

In 1997, irregular emigration of Falash Mura, a group that converted to Christianity under duress but sought to return to Judaism, began. This emigration has been subject to political developments in Israel and has continued to this day.

In August 2018, the Israeli government under Prime Minister Netanyahu pledged to bring in 1,000 Falasha Jews from Ethiopia. In April 2019, an estimated 8,000 Falasha were waiting to leave Ethiopia. Subsequently, small groups of Falasha Jews arrived in Israel, including 43 individuals who arrived on February 25, 2020.

On November 14, 2021, Falasha Jews in Israel staged a protest advocating for the immigration of their relatives still in Ethiopia. In response, the Israeli government decided to permit 9,000 Falasha Jews to go to Israel. On November 29, 2021, the Israeli government allowed 3,000 Falasha Jews to immigrate. As of 2021, a total of 1,636 Jews had immigrated to Israel from Ethiopia.

The Ethiopian Beta Israel community in Israel comprises over 159,500 people, which is slightly more than 1 percent of the Israeli population.

Most of the Ethiopian Jewish population in Israel are descendants of immigrants who arrived during Operation Moses in 1984 and Operation Solomon in 1991. These rescue operations were conducted due to civil war and famine in Ethiopia.

Over time, Ethiopian Jews in Israel moved out of government-owned mobile home camps and settled in various cities and towns throughout the country. The Israeli authorities encouraged this settlement by providing new immigrants with generous government loans or low-interest mortgages.

Ethiopian Jews faced obstacles in integrating into Israeli society, including communication difficulties due to language barriers and discrimination, including manifestations of racism, from some parts of Israeli society.

Ethiopian immigrants arrived from an impoverished agrarian country and were often ill-prepared to work in an industrialized country. As a result, the Ethiopian Jewish community has, on average, lower economic and educational levels compared to the average Israeli population.

Serving in the Israeli Defense Forces has contributed to the integration of young Ethiopian Jews into Israeli society. Military service has provided them with increased opportunities after their discharge.

Despite progress, Ethiopian Jews still face challenges in assimilating into Israeli-Jewish society. They experience higher rates of school dropout, juvenile delinquency, suicide, and depression compared to other communities.

Marriages between Ethiopians and non-Ethiopians are less common. A survey found that a majority of Israelis considered marriage between Ethiopians and non-Ethiopians unacceptable, contributing to barriers to intermarriage.

Ethiopian Jews have faced discrimination and racism in Israeli society. The "blood bank affair" in 1996 highlighted discrimination when blood banks refused to use Ethiopian blood due to unfounded fears of HIV.

Ethiopian Jews in Israel have experienced cultural racism and exclusion, leading some individuals to reclaim their traditional Ethiopian names, language, culture, and music. Some scholars suggest that this is a response to the discrimination they face in Israeli society.